- SCZONE SIGNED DEAL WITH CHINESE INVESTORS FOR IRON PRODUCTS PROJECTS IN EGYPT

- WESTPROP HOLDING LIMITED SET TO EMBARKED ON PIPELINE PROJECT IN ZIMBABWE

- FORMER TOGO PLAYER ADEBAYOR LAUNCH SOCIAL HOUSING PROJECT IN TOGO

- AMANSIE WEST DISTRICT ROAD PROJECT BEGINS IN GHANA

- LAGOS TO CALABAR HIGWAY PROJECT: WHY IT CANT BE ACHIEVED

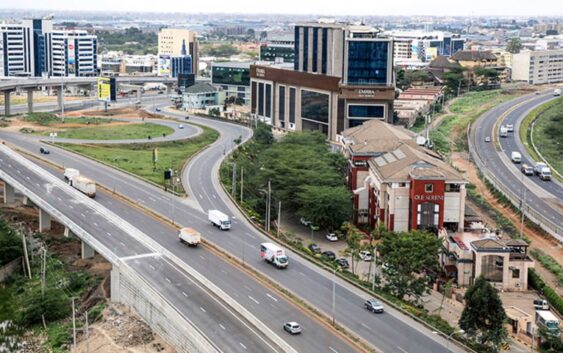

THE IMPLICATION OF KENYA’s CAPITAL CITY ROAD DEVELOPMENT

Some years back, the Government of Kenya explored the possibility of making the 473km Mombasa-Nairobi road a dual-carriage highway. The plan hit a roadblock because it would have required buying land for expansion at massive prices and compensating the owners of high-value buildings adjacent to Mombasa Road, on both sides.

And so, it appeared as though this portion of the critical Northern Corridor would remain the way it had been, for lack of expansion space. However, the problem was eventually overcome.

The construction of East and Central Africa’s first decked road on top of it, in the form of the Nairobi Expressway, has shown that space can be used imaginatively.

What shouldn’t be forgotten is that the Northern Corridor, on which the Nairobi Expressway lies, serves vehicles from East and Central Africa. Vehicles from Tanzania entering Kenya through the Namanga border will at some point use Mombasa Road. Those coming from or headed to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda, use it too. Wouldn’t these countries, all member states of the East African Community (EAC), consider it worthwhile to have Mombasa Road made a bigger carriageway? Wouldn’t that mean faster speeds, shorter time, and cost-savings for their citizens who use this road to especially transport products ranging from farm produce to motor vehicles, to oil?

Various studies have argued that regional integration lowers costs across all aspects of infrastructure. The high cost of infrastructure services in the region is partly attributed to a rigid focus on national boundaries. Viewing infrastructure development from a national perspective, as opposed to a regional perception, prevents the achievement of economies of scale.

It has also been noted that the traffic flows to most of Africa’s national ports and airports are too low to provide the scale economies needed to attract services from major international shipping companies and airlines.

Experts argue that regional collaboration in multi-country hubs can help overcome this problem. Looking at the region as one contiguous landmass that needs critical infrastructure can change matters.

Forty years ago, Mombasa Road served the region with little stress. With time, Nairobi’s population grew massively. Vehicle numbers increased too. Today, more trucks, buses, vans, and saloon cars use this road. And those many years ago – as far back as 1982, for example – Nairobi hadn’t felt the need for the kind of bypasses built in recent years.

Moreover, as East and Central African nations seek to industrialize, their need to import more capital goods, and export more local produce, has been rising. Now, why wouldn’t Kenya and Uganda make joint projections of the expected usage of the Northern Corridor in, say, 20 or 30 years to come, and prepare for that?

In road and rail corridors and transboundary river basins, collaborative management of these regional public goods reduces the cost. Without any doubt, many of Africa’s infrastructure assets and natural resources are regional public goods. These assets cut across national frontiers. Therefore, they can be more effectively developed and maintained only through international collaboration.

Experts suggest that road and rail corridors need to be managed collaboratively to ease transport and trade services to Africa’s 15 landlocked countries. This will help avoid the extensive border delays that slow international road freight to 10km an hour.

Regional infrastructure development involves and requires a high level of trust between countries. Regional institutions are needed to facilitate agreements and implement compensation mechanisms. For example, would South Sudan be interested in knowing how it can help widen the Northern Corridor, and what that would involve in terms of compensation for landowners?

Some countries have more to gain from regional integration than others do. A good example is the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (Lapsset) corridor. How many nations are likely to benefit from the development of a port, airports, and road and rail network passing through northern Kenya to their towns? Developing a route to the sea through these infrastructural networks can make a big economic difference for many nations that neighbor the country.

As long as regional integration provides a substantial economic dividend, countries should be able to design compensation mechanisms that make all participating countries better off.

Unless regulatory frameworks and administrative procedures are harmonized to allow the free flow of services across national boundaries, the physical integration of infrastructure networks will be ineffective. Therefore, greater efforts are needed to facilitate the preparation of complex regional projects that would otherwise be costly and time-consuming to prepare.

Why should Kenya be interested in how Kampala’s or Kigali’s or Kinshasa’s infrastructure is developed? These nations belong to the East African Community and are joined at the hip by the need to get to sea. Moreover, they trade with each other. That’s why the Nairobi Expressway, together with the various bypasses that link with it, matters a great deal in Nairobi, Kenya, East Africa, and even beyond, when you think of the quick access it provides to the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport.

SOURCE: The Nation